Does It Really Matter Where a Piano Is Made?

When shopping for a piano, many buyers start with basic questions—sound, size, and price. But as they dive deeper into research, they’re often met with bold claims from salespeople about where a piano is built. The truth? Most customers don’t begin their search caring about a piano’s country of origin. It’s usually the salespeople—or bloggers posing as experts—who make it seem like a dealbreaker.

A common sales pitch goes something like this: “These pianos are all built the same, and you’re in luck—we carry the one you should buy!”

The reality is simpler: you can evaluate a piano’s quality without obsessing over where it was made. The best use of a salesperson who leans on factory origin as their main pitch is to ask them to remove the front panel, the fallboard, or the bottom board for you. Upright pianos should be pulled away from the wall so you can see the soundboard and backposts. That way, you can inspect what really matters—the design, materials, and craftsmanship inside the instrument. In fact, if you know what to look for, you can spot a better-built piano within your budget and potentially avoid costly repairs down the road.

It is ok to ask – all properly trained piano salespeople know how to do it.

A Case Study: Two Pianos, One Factory

Let’s compare two entry-level upright pianos made in the same factory: the Ritmüller and the Essex. Both are built by Pearl River, one of the world’s largest piano manufacturers. Ritmüller is a Pearl River brand, while Essex is designed by Steinway & Sons and built under their specifications and supervision. Despite sharing a factory, these pianos are worlds apart.

Soundboard Quality

Spruce is the gold standard for soundboards due to its straight grain and efficient sound transmission. On upright pianos, it is easiest to see the soundboard from the back. On grand pianos, you can see the soundboard through the strings inside or from underneath the piano, if you’re willing.

Essex Soundboard

Our subject Essex features a high-quality spruce soundboard—clear, honey-colored, and tonally shaped for richer sound.

Ritmuller soundboard – notice the broken lines.

In contrast, our subject Ritmüller uses what appears to be agathis, a lower-cost wood often found in toy instruments, with no tonal shaping. This alone creates a noticeable difference in clarity and tone.

It can be challenging to notice this without a trained ear or hearing the pianos side by side. Over time, players often tire of the one-dimensional sound produced by low-grade woods like agathis, while the tonal richness and complexity of spruce continues to inspire deeper playing and more satisfying musical expression.

Plate Gap: Supporting Sound, Not Smothering It

In a well-built piano, the heavy cast-iron plate should never press against the soundboard.

Quality pianos like Essex maintain a proper gap, allowing the soundboard to vibrate freely.

Essex shows a gap between the soundboard and plate, allowing the soundboard to vibrate.

Ritmüller, on the other hand, uses wood strips and screws to compress the soundboard—dampening tone and responsiveness.

Sandwiching a block of wood between the soundboard and the plate is part of the Pearl River piano design, but it restricts the movement of the board.

The impact on sound is significant. A restricted soundboard loses resonance and projection, which results in a piano that sounds muted or flat, especially over time. This shortcut in construction might lower manufacturing costs, but it also compromises musical potential.

Frame and Bracing

The Essex has substantial backposts and a reinforced frame—features often overlooked by casual buyers but vital to the piano’s longevity and performance. These structural elements help the piano withstand the immense tension exerted by the strings, which can exceed 40,000 pounds of tension.

The Essex piano (left) features robust backposts and a thicker frame. The Ritmüller (right), lacks backposts and uses a thinner frame with less structural reinforcement.

A well-braced frame resists twisting and shifting over time, preserving both tone and tuning stability. Ritmüller, by contrast, appears to lack this level of reinforcement. Without robust bracing, the piano’s structural integrity may degrade faster, leading to warping, instability, and an overall decline in performance as the years go by.

Bass Bridge Design

The design of the bass bridge plays a crucial role in how effectively the lowest notes on the piano resonate. A well-engineered curved bass bridge ensures that each string contacts the optimal point on the soundboard—what piano designers call the “sweet spot”—to maximize tonal depth and clarity. The Essex achieves this with a carefully arched bridge, reflecting Steinway’s commitment to musical precision.

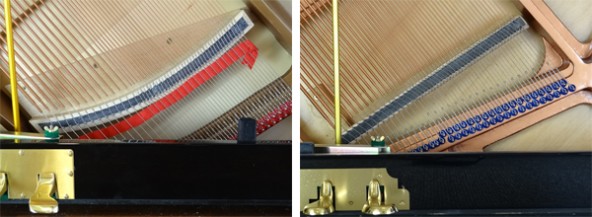

The Essex piano (left) features a curved bass bridge that aligns with each string’s sweet spot for clear, resonant bass. The Ritmüller (right) uses a straight bridge, often leading to muddier, less defined low notes.

In contrast, this Ritmüller employs a straight bass bridge, a simpler and less costly construction method. While easier to manufacture, a straight bridge can result in uneven contact with the soundboard, leading to muddy or dull-sounding bass notes. This seemingly small difference dramatically affects the richness and definition of the piano’s lower register, especially noticeable when playing pieces with deep, sustained chords or powerful left-hand passages.

Action Parts: It’s in the Wood

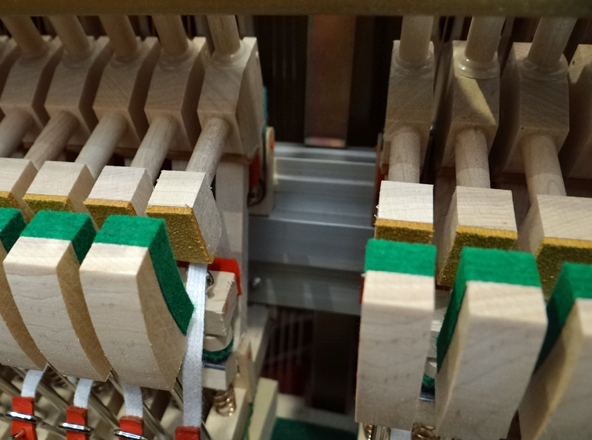

Both pianos use wood action parts, but higher-quality pianos like the Essex demonstrate a level of precision and craftsmanship that reflects a higher standard of design. Its action components show carefully selected, uniformly grained wood that provides both strength and responsiveness—hallmarks of a well-regulated piano action.

Essex Action Parts

This level of detail ensures a smooth, even touch that enhances musical expression and minimizes long-term wear.

Ritmüller Action Parts

In contrast, the Ritmüller uses mismatched cuts of wood, sometimes showing inconsistent grain or end grain spots, which can lead to uneven responsiveness and reduced durability over time. This shortcut in material selection may save costs in manufacturing, but often results in a less satisfying and less reliable playing experience.

Action Rail: The Backbone

The action rail is one of the most overlooked yet critical components in a piano’s long-term performance. It serves as the foundation for the thousands of moving parts in the piano’s action. If the rail warps or shifts, even slightly, the alignment of the hammers and keys is thrown off—leading to inconsistent feel and unreliable response.

Essex Aluminum Action Rail

The Essex uses a modern extruded aluminum action rail, which is stable, durable, and unaffected by changes in temperature or humidity. This design helps preserve the piano’s precision over decades of use.

Pearl River designed wood rail

In contrast, the Ritmüller relies on a traditional wood rail. While historically common, wood is far more susceptible to warping, swelling, or cracking over time, especially in variable climates. This choice can lead to uneven touch, mechanical issues, and more frequent service needs down the line.

So—Does It Matter Where a Piano Is Built?

Clearly, two pianos from the same factory can be very different. It’s not where the piano is built, but how it’s built—and who designed it—that matters most. This applies across many brands: Yamaha, Kawai, Petrof, and others all offer models built to varying specs in different countries. Taking the time to inspect these details for yourself—rather than relying solely on brand reputation—can help you find a better-built piano for less money, especially if you’re not intimidated by a pushy salesperson.

With better-designed pianos like Essex, you’re getting an instrument shaped by decades of engineering and quality control—even if it’s built overseas.

Pianos like this Essex are designed to be truly musical instruments, with features and build quality aimed at delivering a rewarding playing experience. In contrast, many other entry-level pianos are primarily engineered to be cheaper to build.

The best part? You can see all of this with your own eyes. No tools, no tech—just an understanding of what to look for. And if you’ve already put that slick-talking salesperson to work removing panels and lifting lids, then congratulations—you’ve just turned their sales pitch into your inspection checklist. It’s not about taking their word for it; it’s about having them reveal what really matters—sometimes without even realizing they’re doing it.

So next time someone tells you a piano is better simply because of where it’s made, trust your eyes—and your ears. Quality is in the details—the design, the materials, and the craftsmanship—not the country stamped on the label.